According to Praeger no issue has a greater influence on determining your social and political views than whether you view human nature as basically good or not:

I believe that we are born with tendencies toward both good and evil. Yes, babies are born innocent, but not good. Why is this issue so important? First, if you believe people are born good, you will attribute evil to forces outside the individual.

One of these forces is poverty, which explains evil by social deprivation. The fallacy of this explanation is, Praeger points out, that there are people who choose evil for reasons having nothing to do with their economic situation.

He goes on:

Second, if you believe people are born good, you will not stress character development when you raise children. [...] You will teach them how to struggle against the evils of society -- its sexism, its racism, its classism and its homophobia. But you will not teach them that the primary struggle they have to wage to make a better world is against their own nature.

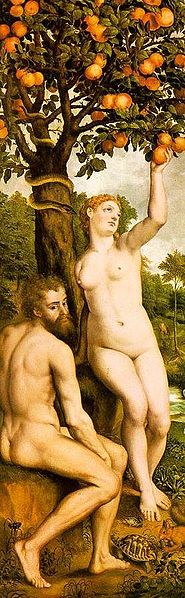

This is what religion teaches, at least the Christian religion does. Mankind is with Adam: we are, like St. Paul, "of the flesh, sold under sin" (Rom 7:14, ESV). If there is something wrong with the society, it is not the society: it is us. It is not the structure we must blame, but the agent.

Praeger continues with two more important points, but we already know where he is coming from. I have always admired the eloquence of the conservative genre: conservatives do not need to quote research or theories to make a point. An argument composed in layman's black/white, either/or, friend/enemy terms communicates more than social science ever could.

Where have I read Praeger's question before? In Carl Schmitt's The Concept of the Political, of course:

One could test all theories of state and political ideas according to their anthropology and thereby classify these as to whether they consciously or unconsciously presuppose man to be by nature evil or by nature good. [...] The problematic or unproblematic conception of man is decisive for the presupposition of every further political consideration, the answer to the question whether man is a dangerous being or not, a risky or harmless creature. (58.)

A theologian ceases to be a theologian, Schmitt argues, when he no longer considers man to be a sinner in need of redemption, no longer distinguishes between the chosen and unchosen. When you first entertain the thought that people can be good, you will soon believe that you yourself are good. Those who disagree with your assessment -- and there will always be someone -- are not merely wrong, but likely to be on the evil's side. Theology works as a bulwark against moral relativism: a stand on God's good against the ideas and ideologies of men.

Praeger finishes off by demolishing the ideological foundations of "secular humanistic culture":

No great body of wisdom, East or West, ever posited that people were basically good. This naive and dangerous notion originated in modern secular Western thought, probably with Jean Jacques Rousseau, the Frenchman who gave us the notion of pre-modern man as a noble savage. He was half right. Savage, yes, noble, no. If the West does not soon reject Rousseau and humanism and begin to recognize evil, judge it and confront it, it will find itself incapable of fighting savages who are not noble.

In other words: political society needs God on its side. Where have I read this before? Joseph de Maistre is about as pessimistic when it comes to the faculties of man in taking care of its political institutions. Considerations on France is an attack on Rousseau -- "perhaps the most self-deceived man who ever lived" -- and the revolution he helped inspire. De Maistre abhorred the idea of state apart from the divine:

It would be curious to examine our European institutions one by one and to show how they are all Christianized, how religion mingles in everything, animates and sustains everything. Human passions may pollute and even pervert primitive creations, but if the principle is divine, this is enough to give them a prodigious permanence. (42.)

Though I agree with Praeger when it comes to his (and Schmitt's) anthropological assessment, I find it difficult to bring it into our political context. Both de Maistre and Praeger write in their own political contexts -- Joseph against revolutionary humanism and Dennis against American liberalism -- and their conclusions have little to contribute to, say, Finland in the current political moment. What (or who) is evil in Finnish society? Is God on Finland's side, and if indeed he is, who are the Finns exactly? If not on "our" side, whose side is God on?

(Via Apologetic Junkie.)

Mika

0 comments:

Post a Comment